Author: Gustavo

Ahmadreza Hakiminejad

Assistant Lecturer

Coventry University

The nation state is not visible, it is … an ‘imagined community’ that must be rendered visible through an iconography of buildings, maps and monuments, often represented on money and stamps, that affirm the story of the nation, enabling citizens to imagine what they cannot see.

– Kim Dovey, 2018

Architecture is not politics, but it serves it unequivocally! It embraces power and the powerful. The states often employ architecture (of symbolism) to demonstrate strength and stability, as the word ‘state’ itself “shares the Greek root ‘sta’ with words like stand, stable, static, statue, statement, standard, stage, status and establish”. Hence, a building can simply be conceived as a means of political and ideological manifestation. With 114 years of history, the Iranian parliamentary establishment has been struggling to function as a democratic means of power to this day. Drawing upon a sociohistorical and political narrative, this piece aims to portray a critical reading of the Iranian power structure, providing a semantic analysis of the parliamentary buildings in Iran, with a particular focus on its most recent edifice accommodating the Islamic Consultative Assembly (Majles-e Shūrā-ye Eslāmī).

Viewing the Islamic Consultative Assembly from Bahārestān Square, one sees a fortification, embodied in a solid, impenetrable pyramid of secrecy. The form of the building conveying a sense of closedness, and a lack of transparency, suits perfectly the Iran’s structure of power. The parliament fails to reflect the voice of a nation as it is the result a carefully-controlled electoral procedure under the authoritarian rule of the Supreme Leader. Through a theoretical approach to power I will discuss in the paper in details, why this is the case.

It is intriguing in a way that the Iranian Parliament, with all its formal determinations to express power and stability, is the most fragile of all in Iran’s convoluted structure of power. It can be seen, in its entirety, as a political instrument at the service of rahbar (the Supreme Leader). As a potential candidate, it would be almost impossible to get into that House, if you simply fall out of favour with the Big Brother. The final say belongs to him; and this is not something personal; the Guardian Council (Shūrā-ye Negahbān) – under the utter influence and rule of the Supreme Leader – supervises elections, and all candidates standing for election must meet with its prior approval. The Council can even withdraw the elected MPs.

Amalia Kotsaki

Associate Professor

Technical University of Crete

The paper attempts to shed light upon the unexplored strands of debate between architecture and parliamentarism in modern and contemporary Greece. It does so by studying the ‘theatres of democracy’, parliament buildings situated within Greek territory.

This research contributes to the interpretation of the evolution of Greek parliamentarism using architecture and space as a tool, an approach which slightly differs from the approaches usually implemented in the field of political research. It brings forward a rare opportunity for the enrichment of the considerations for such a crucial issue.

In Greece of the modern and contemporary era (after the Independence, in 19th and 20th century) seven Parliament buildings have been erected in total: at first, the first Parliaments of liberated Greece after the revolution of 1821 but before the nomination of Athens as capital of Greece in 1836, namely the parliaments of Nafplion and Aegina (first capitals of Greece), then the first parliament in Athens as capital of the Greek State (known as Old Parliament, a neoclassical monumental building designed by the architects F. Boulanger and P. Kalkos) and finally the contemporary Parliament in Syntagma Square in the center of Athens, the Old Palace, a neoclassical architectural synthesis (19th century) by the architect F. Gärtner, which became the Parliament after an immense transformation of its interior (1954).

There are also the Parliament of Cretan State, the Parliament of the United States of the Ionian Islands and the Parliament of the Principality of Samos, monumental buildings designed especially for parliaments. However, these parliaments haven’t been constructed from Greek local authorities but from the states that these semi-autonomous regions belonged. Crete and Samos were semi- autonomous tributary states under the Ottoman suzerainty and Ionian Islands under the British. (Crete until 1913, Ionian Islands until 1864, Samos until 1912).

The spatial construction of all these Parliaments in Greece, totally different between them and in reference to the Parliaments of London ( Parliament of the United States of the Ionian Islands, Corfu) and Istanbul (Parliament of Principality of Samos), proves Greece as an ideal field for research of the relationship between architecture and parliamentarism. In parallel, this fact appears as a good opportunity for the research of the relationship between a suzerain and a tributary state.

The paper will attempt the presentation of these parliaments with an effort to interpret the distinct differentiations of their architecture by comparing each parliament with the parliament of the suzerain state and with parliaments of other semi autonomous tributary states under the same suzeraingty. (Ionian islands, Malta, London Parliament_ Samos, Plovdiv (East Rumelia), Istanbul Parliament).

Which were their prototypes, ancient and modern?

Which were their references to the parliamentarian architecture of the suzerain states?

How do they express the versions of parliamentarism that each of them is housing?

Is the differentiation of their spatial construction expressed on their facades? If not, how can we interpret it? What precisely is the role of neoclassicism?

How do all these spatially different parliaments have structured political practices and how these practices have influenced greek parliamentarism after the Unification of these semi- autonomous tributary states with Greece?

Andrew Borg Wirth

Masters Graduate

University of Malta

Michael Zerafa

Architecture Graduate

University of Malta

The last two months of 2019 saw great political turmoil in Malta as a suspect in the Daphne Caruana Galizia assasination was identified and connected to members in the highest position of the Maltese Government. As from the day the public found out about the suspect, November 21st, protests were organised in Valletta everyday, in front of Parliament, the Office of the Prime Minister and the makeshift memorial which was put together for the late journalist, calling for accountability and demanding resignations from anyone who is implicit.

All three protest spaces meant different things to the protestors, with the parliament square being the most popular because of the direct agency it gives protestors to make parliamentarians listen whilst a session is going on. Recently designed by Renzo Piano, the ground floor area of the building was intended to be fully transparent and accessible by the public: politicians would share the same entrance with anyone else. The configuration and materiality of the ground floor used by the architect was a symbol for an open and fair democracy, giving people the opportunity to stop politicians on the way in and out of parliament – a gesture meant to portray the sort of accountability which politicians should have to the people they serve.

As time passed and revelations about the assasination grew, so did the crowds that would congregate – progressively bigger, undeniably louder and tangibly more disobedient. Police presence increased and layers of barricades were added between protestors and parliament from week to week. By December 2nd, the 25m wide parliament square was closed off with barricades, with a significantly increased number of police behind them. Only a narrow corridor opposite parliament left for public use. The protestors were enraged.

People knew that parliament was in session; they understood that denying access to one of the largest squares in the capital didn’t bode well; they were infuriated by politicians not facing them, escaping from back entrances and vanishing in fleets of black cars.

One night, and quite spontaneously, the crowd took matters into its own hands: the politicians tried to lock them out of their public space, so they locked the politicians inside parliament.

In a collective effort, the public gathered in front of the main entrance to the parliament, spreading to the different exits of the buildings which led to other squares, streets and the city’s ditch. All televisions in the country showed one incredibly weird scene: politicians stuck in a glass box, surrounded by a cage of barricades which they built for themselves and locked by the people they wanted to keep out. It was a spectacle of power, a direct expression of collective anger and a display of one of Piano’s best design decisions: to unravel the veil that transparently hangs between public and private life. His was a decision to expose and seek clarity.

The ‘Malta’ this Parliament Building had been planned (and built, inaugurated and launched) in isn’t the same one it is today – in many ways, because of it.

Kathryn Rix

Assistant Editor Commons (1832-1868)

History of Parliament

In 1847 The Times suggested that ‘in the eyes of the people generally, and of their constituents in particular’, having accurate information about how their representatives voted in the division lobbies at Westminster was ‘of far greater importance than a thousand speeches and the most elaborate displays of eloquence’. For many MPs, not least the numerous silent members of the nineteenth-century House of Commons, their most significant contribution to parliamentary business came not in the visible arena of the debating chamber, but the more confined spaces of the division lobbies. Yet while the physical act of voting with the ‘Ayes’ or the ‘Noes’ took place away from the public gaze, the publication of official division lists from 1836 onwards meant that MPs’ actions within this particular parliamentary space could readily be subjected to scrutiny.

The compilation of more accurate division lists for official publication, in contrast with the unofficial lists previously produced, was facilitated by a significant alteration to the architecture of the House of Commons. In 1836 a second division lobby was added to the temporary chamber in use following the famous fire of October 1834, which had destroyed much of the old Palace of Westminster. Before this date, the presumed minority on any question had gone out of the Commons chamber into a single lobby to vote, while the presumed majority had remained in their seats. The fact that two separate division lobbies first came into existence thanks to this adaptation of Parliament’s temporary accommodation has received little attention in histories of Parliament.

This paper considers the factors which prompted the development of this new parliamentary space, looking in particular at the impact of the 1832 Reform Act on perceptions of MPs’ representative functions. It also reflects on the new opportunities which the temporary House of Commons offered as a site of architectural experimentation and innovation in catering for the needs of 658 MPs in the post-Reform era. Alongside the second division lobby, other new features tried out in the temporary Commons included a separate press gallery and a ladies’ gallery. The two lobby system trialled in the temporary House was subsequently incorporated into the new Palace of Westminster designed by Charles Barry. The division lobbies were among the facilities given a test run in May 1850, ahead of the new Palace’s official opening in 1852. While voting was the key activity which took place within these lobbies, pressure on space on the parliamentary site meant that they also had other, less formal, functions.

Having analysed the reasons for these adaptations to the physical space of Parliament, this paper assesses the ways in which this shaped MPs’ behaviour, both within the confines of the Commons, and in their relationship with their constituents. By enabling the publication of authoritative division lists, the two lobby system focused greater attention on MPs’ levels of attendance (as highlighted in ‘league tables’ published in the press) and their voting record on particular subjects. This had important implications for the development of the two-party system and in shaping the interactions between politics at Westminster and in the localities, key factors in understanding the evolution of the modern British political system.

Robin Eagles

Editor of the House of Lords (1660-1832)

History of Parliament

One of the most admired features of the old House of Commons were the galleries erected by Christopher Wren in the late 17th century. Visitors appreciated their elegance and they provided much-needed additional space in the otherwise cramped conditions of the former St Stephen’s chapel. There have recently been new insights into these structures and the people who were able to gain access to them by Paul Seaward, and by the ground-breaking research of the St Stephen’s Chapel project.

Much less attention has been paid to the ill-fated galleries that were erected in the House of Lords on three separate occasions in the 18th century. Like the Commons, members of the Lords complained frequently of the conditions in which they were required to deliberate and of the occasional ‘inconveniences’ caused by MPs, members of the public and other interlopers attempting to gain access to their chamber. To solve this, under Queen Anne, George II and again under George III orders were given for the construction of galleries to increase the capacity of the chamber and offer privileged outsiders the opportunity of observing proceedings at a respectful remove.

On each of these occasions, the galleries survived for just a short time before being torn down. Unlike in the Commons, the members never warmed to the additions, complaining that they took away their light, or encouraged non-members to invade what they considered to be privileged space.

This paper will consider the circumstances under which these galleries were constructed, those in favour of the alterations and who argued strongly against. It will assess the practicalities of tacking on new structures to a chamber of largely mediaeval design and the response to the innovation more widely.

At the heart of the paper, though, will be the concept of privilege. Ever since the Lords had been restored in 1660 the question of their privilege had been to the fore in their deliberations. On numerous occasions there were complaints about non-members taking up space that should have been reserved for the Lords and Bishops and concerns about ensuring that the Lords were accorded proper respect and distinction when meeting with members of the lower house.

The construction of galleries revived the issue of the privileged space of the Lords and to what extent it was thought reasonable, or desirable, for non-members to observe the Lords’ proceedings. When the Commons finally gave way over press reporting of their debates following the Printers’ Case in the 1770s, it was noticeable that the Lords attempted to hold out for several more years before finally bowing to the changing circumstances. Thus, was the Lords’ objection to what should have been thought of as an improvement to their environment more to do with a consistent reluctance to adapt, and insistence on their continued exclusivity, rather than concerns about the practicalities of constructing ungainly structures within a confined space? Examination of the Lords’ galleries will provide a more complete understanding of the Lords in the period and how they viewed their role within Parliament.

Gordana Fontana-Giusti

Architect, Urban Designer and Professor

University of Kent

The two main aims of the conference are weighty and thought-provoking. Addressing the role of politics in architecture and in architectural theory is highly relevant although challenging to take up due to its proximity to the politics of institutions such as universities, professional associations and others. On balance, I shall address them indirectly, as my paper is more geared towards the second aim that leads to more metaphysical questions on theorizing the place of architecture and spatiality within human sciences, which I aim to do by grasping the spatial effects of architecture on individuals and on society. In this way, I seek to contribute to the overall project of analysing the ways in which spatial relations have been designed, constructed and used by architects, users and various agents of power, to instil a set of ethico-aesthetical values and hierarchy of order.

The background to this paper is my long-term research relating to: Michel Foucault who has explicitly addressed this agenda in his Discipline and Punish, Lewis Mumford who grappled with these questions within the context of urbanism and the city in history, and a number of architectural treatises such as those by Vitruvius, Alberti and Serlio where many pertinent aspects of this discourse could be found. More specifically the recorded correspondences that occurred during the design and construction of parliamentary buildings are another important primary source of documents. Due to architecture’s predominant focusing on the formal values of an architectural object, more metaphysical aspects related to the spatial effects and spatiality of buildings have systematically achieved less prominence until what came to be known ‘the spatial turn’ exemplified in the seminal texts by Foucault, Derrida, Deleuze and Guattari, Virilio and others.

In this context parliamentary buildings provide a series of distinct case studies – a particular typology – of edifices containing special significance for their nations due to their all-encompassing role and emblematic status, where the aura of their symbolism is constantly disseminated via proliferation of images, films, television programmes and other digital media spinning the appearances of the edifice ad infinitum.

The paper will focus on spatiality, its implicated logic and the effects within the structure that is the symbolic home for the nation. This is an under-theorised area of architectural theory that deserves further scrutiny. Indeed, the work of conceptual artists such as Christo & Jeanne-Claude and Langlands & Bell have put forward the concerns, apprehensions, fears and perplexities in respect to institutional spaces of this kind.

In this paper I therefore aim to investigate the following three aspects: a) the status of ‘debate’ as a philosophical category and to query if there is a need for the provision of a specific architecture and if so why and how? The notion of the (parliamentary) debate itself needs to be questioned: what is going on in a debate? Disagreements / a range of disagreements? Or an attempt to achieve consensus which is often a difficult or an impossible task to do? In this context I shall recall the discourse on Kant’s transcendentalism given that the ideas that underline the eighteenth-century project of Enlightenment came to underpin the emergence of parliamentary democracies and the form of their edifices; b) trace back the conditions of the variety of basic models of congregation that became dominant spatial prototypes for parliaments and c) draw conclusions about the nature of debate, the epistemological need for its architectural framing and the nature of edifices that materialised, with reflection on the prevalent choices and their blind spots.

Sam Griffiths

Associate Professor in Spatial Cultures

The Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL

In a passage from his 1845 novel Sybil the future British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli (1804–1881) refers to the home of Britain’s Parliament in the Palace of Westminster as “those proud and passionate halls”. If this view seems at one with the romantic sensibility of the Victorians towards old buildings, it would be wrong to think that it extended to the ancient institution of Parliament itself, “that rapacious, violent and haughty body”, as Disraeli describes it. He concludes the passage with the rhetorical question “Could the voice of solace sound from such a quarter?” (p.302) The solace Disraeli seeks is from the social discord of utilitarian political economy, the urban-industrial creed in which he sees the traditional pastoral relationships of aristocratic society being replaced by the instrumental relationships of Thomas Carlyle’s “cash nexus”, characterized by the opposing interests of labour and capital.

Disraeli is sympathetic to Parliament only insofar as it fulfils what he regards as the institution’s proper role to defend the aristocratic ideal of the commonweal. His ‘Young England’ trilogy Coningsby (1844), Sybil (1845) and Trancred (1847) are set in the years immediately following the passing of the ‘Great’ Reform Act of 1832 that extended Parliamentary representation to the new industrial cities and the franchise to the urban middle class. The Act is typically (if misleadingly) represented as marking a decisive break with the aristocratic government of the English ancien regime, setting the country on the road to becoming a modern Parliamentary democracy. For Disraeli however, the reformed Parliament was not a source of solace but of faction and strife.

It is notable that the fire that consumed most of the medieval-Tudor Palace of Westminster in 1834, and which led ultimately to Barry and Pugin’s neo-gothic Parliament building – a rebuild that would have been underway for almost a decade by the time Disraeli was writing Coningsby ¬– does not merit even a passing mention in the Young England trilogy. For Disraeli the political locations that mattered most lay beyond the Parliament building, particularly the outdoor sites favoured by the working-class Chartist movement. The politics of the ancien regime itself had always taken place in the country houses and clubs frequented by the aristocracy. Indeed, Parliament itself was little more than a club with rules of membership that rapidly promoted boys with aristocratic patronage from the debating societies of Eton and Oxbridge to the Parliamentary stage.

It is not hard to find contemporary parallels. Kim Dovey (1999) has argued that Parliamentary debating chambers constructed to the Westminster template of two opposing sides facing off at “swordfighting distance” (p. 92), and with a clear hierarchy of front-bench to back-bench seating, help encode patriarchal, conservative tendencies on both sides of the political divide. While Disraeli would not have couched his arguments in terms of architectural design he would have recognized Dovey’s broader point that time-honoured Parliamentary rituals can become a hindrance to the practice of meaningful politics.

Yet if the arguments for Parliamentary reform in Disraeli’s time implied the expansion of the political nation, in contemporary Britain they coincide with the hollowing-out of the (middle-class) political nation. In the context of rapid globalization, Parliamentary buildings as grandiose symbols of nation-states occupying central locations in capital cities, can seem hopelessly anachronistic; ailing monuments to the bourgeois society that Disraeli so distrusted. And what of the ritualized practice most associated with these buildings, namely debates? Increasingly the political forum that matters is the ‘democratic’ virtual space of social media. On this platform the liberal celebration of debate – so far as this implies rational and critical scrutiny of political claims – loses its privilege to define what is, and what is not, politically acceptable argument. This paper explores the relationship of the Parliamentary buildings to political agency in the ‘Young England’ novels of Benjamin Disraeli and develops the comparison between the political juncture of 1832 in Britain and the current crisis of parliamentary legitimacy in which ‘voices of solace’ can seem suspect.

Harald Trapp

Architect and Exhibition-designer

UAC Skopje

The Teutonic Thing, one of the earliest political forms, is a gathering. It unites the corporate body of the assembled warriors, the place, its marking through stones or twigs, the issues to be negotiated and the process of their consultation and decision. Spatially the circle of the Thing is the interaction of a form of bodies with a form of objects, that distinguishes an inside from an outside. Even if, according to Heidegger, only the “contested matter” seems to have remained in the German word “Ding” (or the English “thing”) from the Thing, in its entirety, as Heidegger writes, it originally intends to “appropriate the fourfold”.

The gathering Thing not only has, but operates through a physical form, though not yet producing an architectural enclosure. Such a space first appears with the differentiation between open-air assembly and enclosed council in ancient Greece and Rome. The latter extends the Thing to the architectural form of the Bule or Curia, now three-dimensionally distinguishing an interior from an exterior space to facilitate a secluded debate. However, the complexity of classical political order proves to be vulnerable in the course of history, overwhelms the structures available and ultimately leads to their dissolution. Historically, therefore, the rule condenses in the king in a kind of regression through concentration, in which the difference between the ruling and the ruled is to be resolved.

Once sovereignty has been concentrated in the hereditary monarch and the metaphysics of divine grace, the king´s two bodies become the Thing, which merely appropriates architecure to supplement its power through representation. To overcome this autocratic rule of a body and with it, the “zoology of the aristocracy” as Marx called it, the French Revolution installs the assembly of citizens to articulate and represent the volonté générale. Extraordinarily, the non-specificity of the national convention´s initial spaces is able to gather the interaction of bodies and objects into a complex architectural system.

From the Salle de Menus Plaisirs, to Jeu de Paume, Champ de Mars, Salle du Manege and the Salle des Machines an architectural discourse evolves about the relations between the form of gathering, both as the arrangement of the representatives, its spatial reification as an architectural layout, and the production of the general will. The ensuing evolution between the “the circle of discussion and the semicircle of criticism” cannot be reduced to the development of an “environment”, but acknowledges and implements the material gathering as an equal agent in the production of political decisions. During that short period of time, architectural representation is secondary and not explicitly developed, as representational politics equates representativity. Only upon its institutionalisation, the desire to be symbolically represented becomes of growing importance to the National Assembly and a classical facade is added to the Palais Bourbon: the “Thing” finally becomes a monument.

This paper continues the research started in 2014 for our Venice Biennale project “Plenum – Places of Power” at the Austrian pavilion and discusses the connectivity between architecture as a gathering and gathering as a political process. Taking the spatial production of the “general will” during the French revolution as a unique precedent, it investigates the potential of the organisation of representation and the representation of organisation in architecture.

Tormod Otter Johansen

Researcher at the Law Department

University of Gothenburg

My paper aims at exploring the symbolic aspects of the Swedish state through a case study of the Swedish parliament, the Riksdag and its main ceremonial practices as well as their architectural and material symbolic framing.

The modern Swedish state is a peculiar beast, both seen and self-identified as a modern, rational, and secular institution with the welfare state of the 20th century as its crowning achievement. But it is also one of the remaining constitutional monarchies with a significant symbolic and cultural capital tied to the royal family and the historical provinces with characteristics defined during the national romantic era. The archaic symbols of national romanticism, hereditary power, and a history of warfare and regional domination are in Sweden combined with a specific strand of modernity in the social-democratic project, industrial achievements, gender equality, sexual liberation, scientific prowess, and late 20th century developments like multiculturalism.

The Riksdag is the primary focal point of this complicated backdrop. In both architectural and ceremonial structure, the building and the activities in it relate directly to the conjunction between the modern and archaic elements of the Swedish state and its both formal and material constitution. This is apparent both in everyday parliamentary business and not least in the ceremonious opening of the parliamentary year.

When the Riksdag gathers every September, the Speaker of the Riksdag welcomes the King and his family who arrive in gilded wagons from the Royal Palace. The Speaker accompanies them to the Assembly hall, on the way encountering representatives from all provinces clad in folk costume holding flags and playing folk music. The Assembly hall is decorated with a sober birch veneer, the material that covers most surfaces in public agencies in Sweden. The wall behind the Speaker features the artwork “Memories of a Landscape” woven with linen threads from every province of Sweden. It is flanked by a Swedish flag and a decorated ballot box also representing abstract landscapes with water, land, and roads.

Many important details are found in the ceremonial forms of parliamentary business. When the King enters the Assembly hall, the members of the Riksdag and the audience stands. After that “The King’s Song” is sung, before the national anthem. On ordinary days the Speaker faces the members and bows when entering the chamber. All these ceremonial forms together form what a secular liturgy of the public and political institution.

My interest in studying this secular liturgy of the Swedish parliament relates to my public law perspective and connects to the meaning these symbolic aspects hold in relation to Swedish constitutional history.

Some studies focusing on the physical and symbolic staging of the juridical have been conducted in Sweden, particularly focused on criminal law and procedure. However, within Swedish public law, remarkably little interest has been shown to the symbolic practices of major public institutions.

In international research Philip Manow’s In the King’s Shadow: The Political Anatomy of Democratic Representation (2008) stands out as closely related to the theme I am focused on in this project. Manow compares, among other things, the placement of members in different parliaments and links this to the symbolic transfer of the monarch’s body into the democratic paradigm.

Giorgio Agamben has asked the curious question: “Why does power need glory?” (Agamben The Kingdom and the Glory 2011) This question, which Agamben addresses through a genealogical study connecting glory to the economy of power and its theological roots in the West, seems particularly pertinent in the case of Sweden. While the few details I have described above exposes the ceremonial nature of the exercise of power, the self-image of Sweden is still a secularized, rational, and common sense based form of political society. What form do the ceremonies of power take in a society that has rejected the explicit glorification of its power? The subdued tones of birch veneer seem to act as a more forceful glorification of the supposedly humble Swedish nation than marble columns or soldiers standing at attention would.

Naomi Gibson

Architect and PhD candidate

The Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL

Sophia Psarra

Professor of Architecture and Spatial Design

The Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL

Gustavo Maldonado

Architect and Spatial Data Researcher

MSc Space Syntax: Architecture and Cities, UCL

National parliament buildings have both symbolic and practical roles as seats of power; they define political cultures and contribute to notions of national identity. While political decision-making and governance increasingly take place in a range of spaces and buildings, two historically important spaces – the plenary hall and the parliament building’s site – remain of symbolic significance. These are sites of political theatre, spaces for the formal enactment of debate, voting on legislation, ceremonial addresses and public demonstration. These spaces shape and form the backdrop to forms of political performance which are engaged with by the general public, both in person and through visuals broadcast, published and shared. These are two spaces where democracy at a national level is ‘seen to be done’.

While plenary halls and parliament buildings have been studied, it is rare that these have considered the relationship between the architecture and political culture; how parliament buildings shape political processes and how they express the ideas they stand for. Architectural studies of parliament buildings have typically been straightforward records of plenary hall typologies, architectural styles and forms, without considering how such buildings are performed by politicians and the public. Conversely, social studies of parliament buildings have been largely discursive and not shown how their observations overlay and play out in space. This paper brings together the architectural, spatial, cultural and behavioural, showing the relationships between parliament buildings and people, architecture and events.

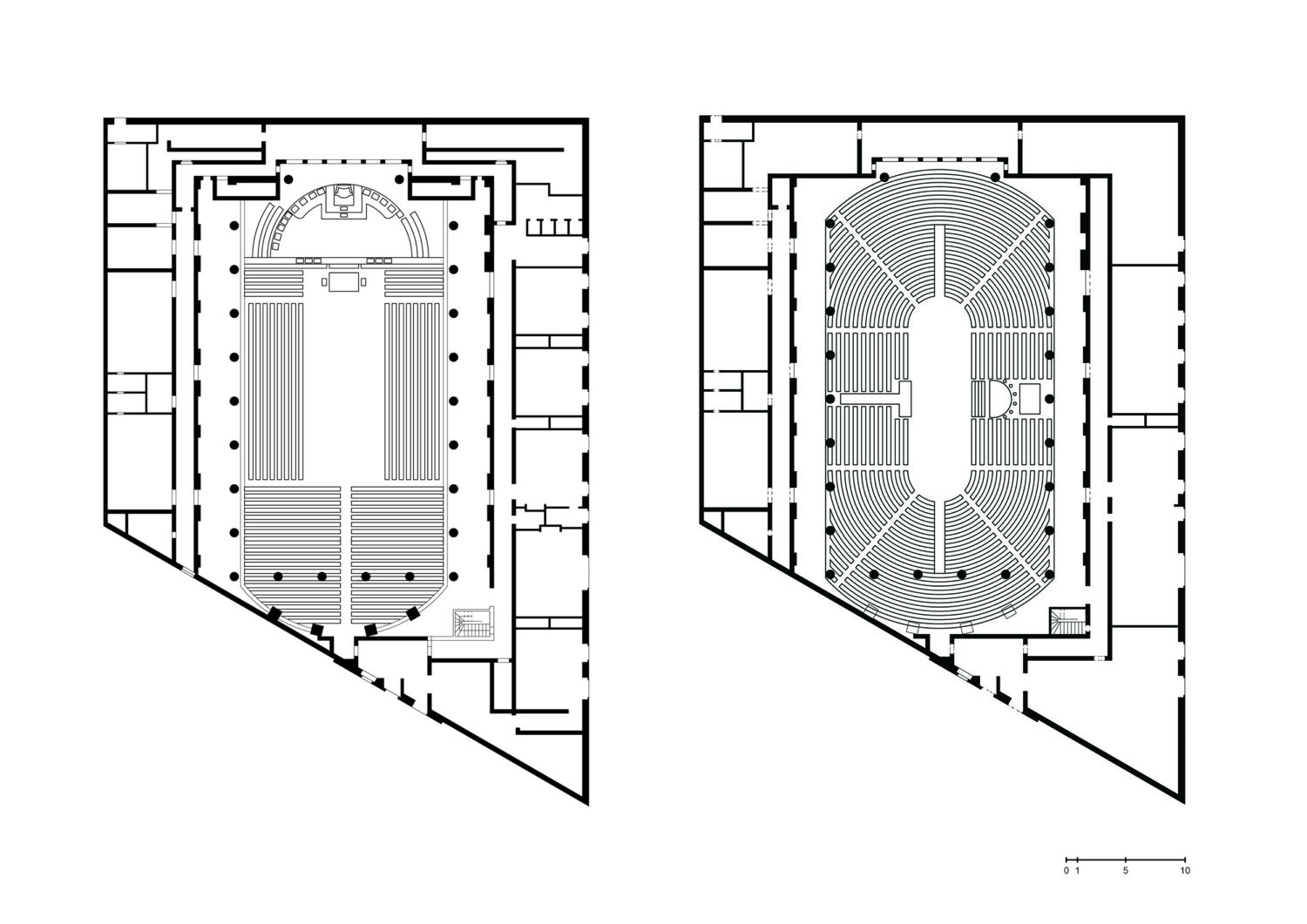

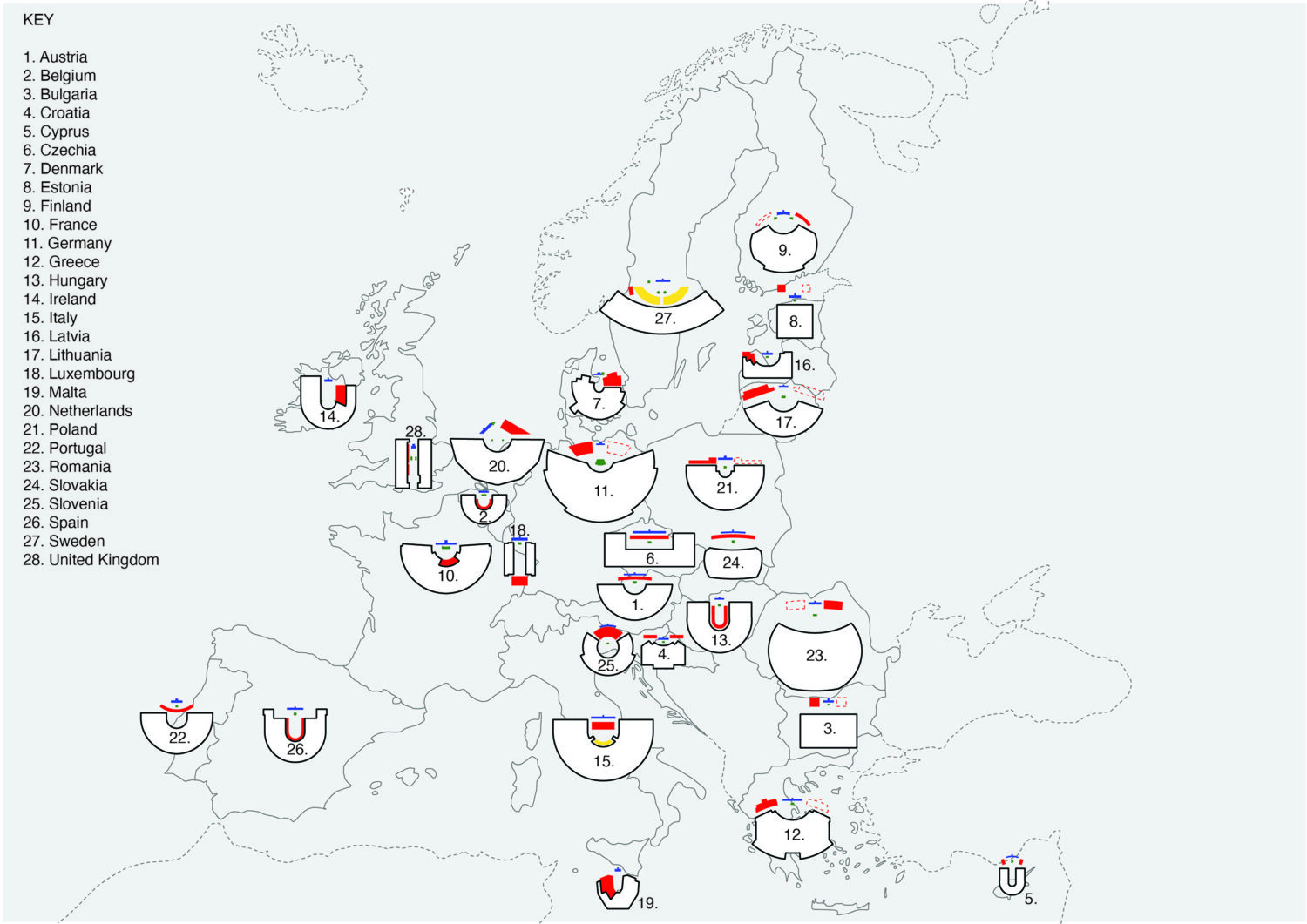

Comparative studies of national parliament buildings have also been few. While parliament buildings are seen as expressions of national identities, comparative studies have demonstrated that common threads link different parliament buildings and their processes. Notable examples include XML Architects’ study of the plenary hall typologies of all 193 national parliaments, and Charles T. Goodsell’s 1988 paper The Architecture of Parliaments, which offers a global overview of parliamentary architecture and political cultures. However, while such studies have managed to isolate and demonstrate broad themes that parliaments may have in common, they neglect the nuance and complexity that a deep, multi-layered, interdisciplinary, systematic comparative study can provide, and which this paper looks to provide.

The 28 national parliaments of EU member states including the UK provide a rich testing-ground for this interdisciplinary comparative approach. This is a group of nations with distinct identities, but which hold shared democratic principles as a condition of their membership as well as deeply intertwined cultures and histories.

The paper comparatively considers the expression and spatial shaping of national identities and politics both inside and outside the parliament buildings, primarily through their sites and plenary halls. First, outside, through principal façades, site plans and social-political histories. While considering the web of architectural languages, motifs and public spaces that go some way to define national parliament buildings, one must consider the origins of the building and the social history it is a part of. While some national parliament buildings are purpose-built, others are adapted for the purpose at a pivotal moment in a nation’s history. Some were selected as a temporary home or out of convenience. Some nations, such as Romania and Slovakia, have complex relationships with their parliament buildings, as they are reminders of the earlier, now overthrown, political regimes that built them. The values and ideas expressed by the architecture is not straightforwardly representative of the political values of that specific nation, or a history they wish to symbolise and continue.

Next, inside, through an examination of building plans and parliamentary procedures with a specific focus on the plenary halls. Within the plenary hall, we argue the shaping of political cultures and relationships goes beyond the five typologies associated with seating for parliamentarians – of the opposing benches, semi-circle, circle, classroom and horseshoe. Rather, there isn’t a strict uniformity in the way each typology is performed. This becomes clear when taking into account the spatial relationships between the executive body and parliamentary representatives; where people stand to speak and the location of people they are speaking to; how parliamentarians vote and the visibility of this action; who is allowed to observe these procedures within the space, and where these observers sit.

This paper, by providing a comprehensive visual, spatial and social study of European national parliament buildings demonstrates why interdisciplinary approaches to the study of parliaments matters. It shows how the meaning of parliament buildings can be read through their social-political histories and the political implications of their architecture seen through studying the way in which they are performed. Ultimately, it shows the complex relationship between national parliament buildings and the people they represent.