Tommaso Zerbi

Historian of Architecture

University of Edinburgh

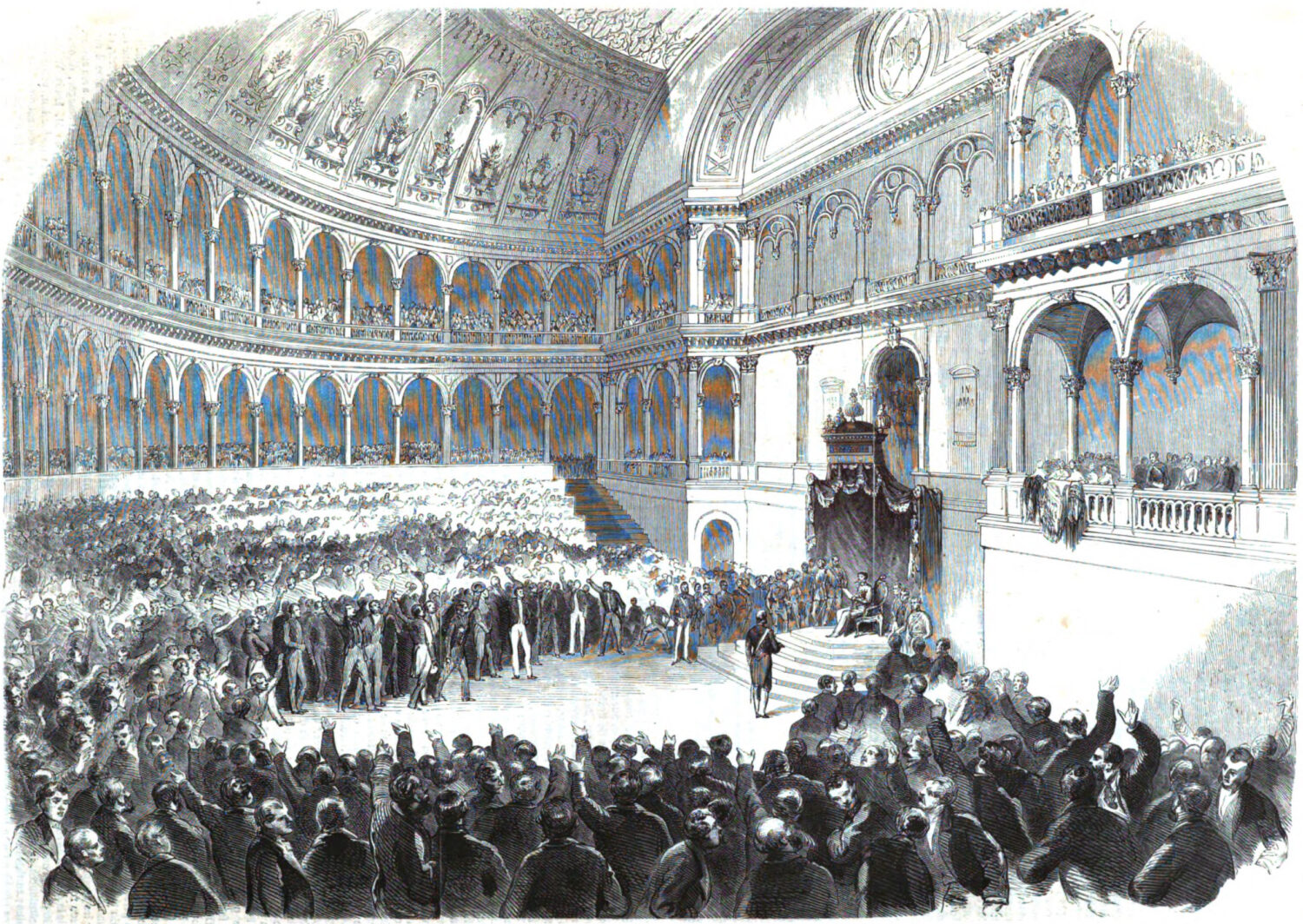

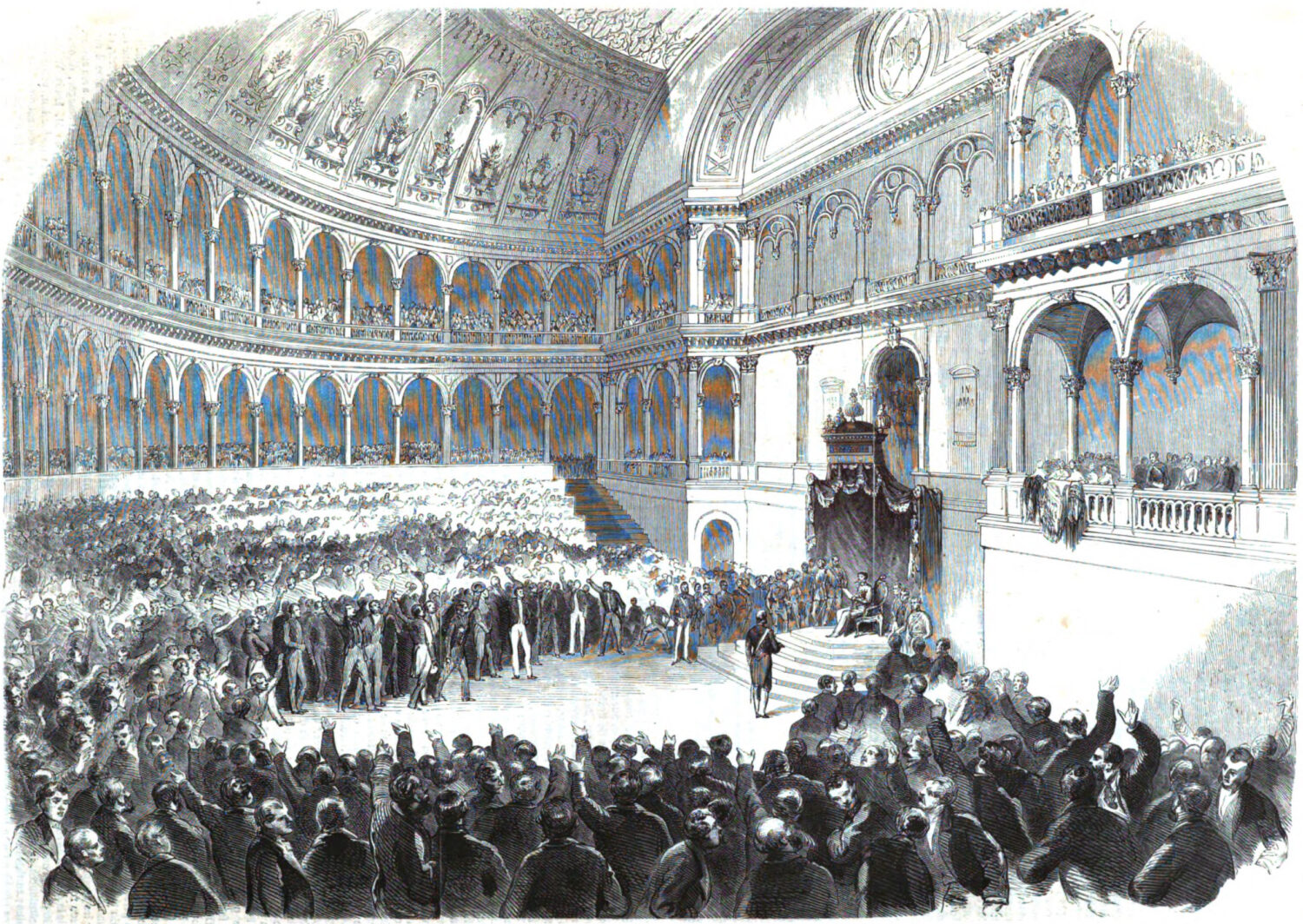

‘Today, the eighteenth day of February of the year one thousand eight hundred sixty-one, reigning Victor-Emmanuel II, the Italian Parliament opens in Turin.’

On that day, Victor-Emmanuel II of Savoy-Carignan opened the first sitting of the Italian Parliament. On 17 March, the last King of Piedmont-Sardinia was proclaimed the first King of Italy. These key moments in the construction of the Italian state took place in the chamber that had been built at the rear of Palazzo Carignano to temporarily accommodate the growing number of the deputies of the Subalpine Parliament. The ephemeral architecture that hosted the first Italian Parliament in Turin between 1861 and 1865 — and demolished with the transfer of the capital to Florence —, offers an insight into a wider concern then prevalent in Piedmontese politics to constitute relations between the new Italian state and the Crown of Savoy. In cross-disciplinary dialogue with architectural history, medievalism, and modern Italian studies, this paper reveals the unexpected role of medievalist ephemerality in the exercise of power and in entwining national and dynastic narratives during the Italian unification.

If parliamentary architectures, as Goodsell put it, ‘are themselves artefacts of political culture,’ the history of modern Italy is rich in such artefacts. In Turin, one thinks of Palazzo Madama and Palazzo Carignano, that were chosen to host the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies of the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia. With the transfer of the capital to Florence (1865) and Rome (1871), the House of Deputies moved first to Palazzo Vecchio and then Palazzo Montecitorio, whilst the Senate moved to the Uffizi and then Palazzo Madama (in Rome). By hosting the first sitting of both the Subalpine Parliament (1848) and Italian Parliament (1861), among this array of architectures Palazzo Carignano is a foundational emblem of constitutional power.

The discipline has produced a great deal of scholarship on Italian state architecture, with a focus on permanent examples. Attention has been directed at the Guarinian Hall in Palazzo Carignano, also known as ‘Aula del Parlamento Subalpino’ because it hosted the Subalpine Parliament (1848–1860). One can also point to the intervention of Domenico Ferri and Giuseppe Bollati for the realisation of the permanent seat of the Chamber of Deputies of the Kingdom of Italy at the rear of the palace (1864–1871). Yet, partially due to a larger historiographical issue for which permanence seems to be favoured over ephemerality as a subject matter of architectural history, less attention has been given to temporary solutions. This is the case of the so-called ‘Aula Comotto’ in Palazzo Montecitorio — the first seat of the Parliament in Rome — and, in Turin, to the building that, hosted the first Italian Parliament.

This paper provides a fresh look on the neglected ephemeral construct, locating it against the backdrop of the delicate transition between the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia to that of Italy. The first part will introduce the project and consider the dialectical symbiosis of engineering and revivalism. The second part will locate it within a wider programmatic reworking of the Middle Ages. By then probing the dualistic nature of the project, the third part will claim that it had central roles in the attempt to forge the intertwined imagery and identities of the Crown and nation. The paper will close with a consideration on the legacy of the ephemeral edifice.