Henrik Schoenefeldt

Professor of Sustainability in Architectural Heritage

University of Kent

Societies since the industrial revolution have naturally been obliged to invent, institute or develop new networks of such conventions or routine more frequently than previous ones. Such networks of convention and routine are not ‘invented traditions’ since their functions, and therefore their justification, are technical rather than ideological. (p. 3)

Eric Hobsbawm, The invention of traditions (Cambridge, CUP, 2012, p. 3)

The two debating chambers of the Palace of Westminster are equipped with sophisticated technologies. In the case of the House of Commons, which was rebuilt after the war, it was an elaborate system of mechanical ventilation and air-conditioning. This superseded the 19th-century system of Charles Barry’s original debating chamber. In addition to adoption of advanced technologies, parliament established, trialed and refined a set of socio-technical practices that enabled staff, MPs and Lords to participate in the day-to-day management of the environment. It enabled them to feedback back their experiences and expectations regarding the climate and air quality in the chamber. This was facilitated through a network that was composed of users (MPs and Lords) as well as technical and non-technical staff. If viewed through the lens of actor-network-theory, staff, MPs and Lords were actors within a wider socio-technical network of environmental control.

These practices had the characteristics of what Hobsbawm describes as ‘networks of convention and routine’. These networks have been forming part of an institutional culture for over 184 years, and they evolved in response to both technological and institutional changes. Their design was also subject of formal reviews in different stages of the technological history of the chambers, leading to revisions of existing and the introduction of new practices.

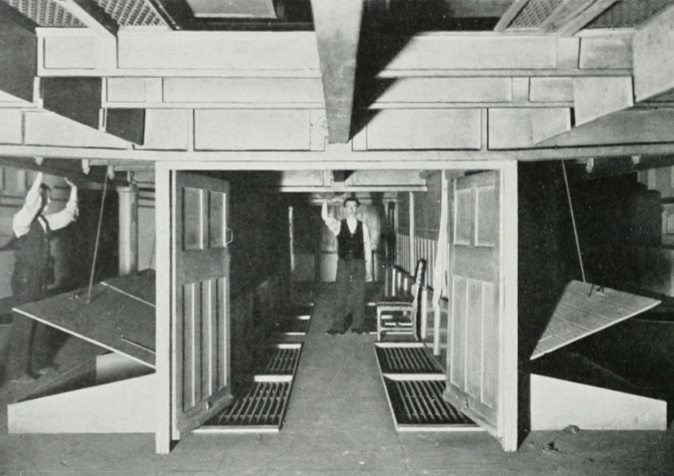

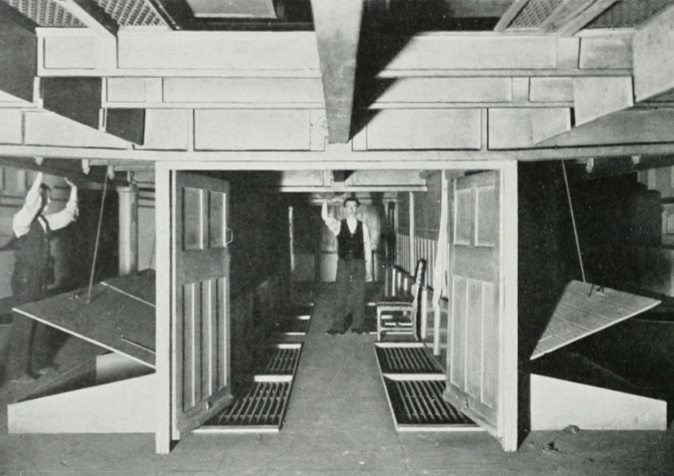

The earliest frameworks were developed and trialed in the temporary Houses of Parliament between 1836 and 1851, before they were introduced into two new debating chambers of the Palace of Westminster, first in the House of Lords, which opened in 1847, and second in the House in Commons, which opened in 1852. In both chambers these practices were revisited and adapted in 1854 in response to technological alterations. In the House of Commons they were re-examined and revised in 1950 and again in the 1990s, in the House of Lords in 1966. These procedures of day-to-day engagement were complemented by larger inquiries coordinated by Select Committees. In these MPs and Lords collaborated with engineers and scientists to study and improve the environment, focusing primarily on questions of user-experience. Figure 1 is a reconstruction of the mechanisms of user engagement followed in the House of Lords between 1955 and 1966, which underpinned the development of a modern air conditioning system.

Using historic records as well as interviews with current staff, MPs and Lords, this paper provides a reconstruction of the social process and retraces their evolution over the period from 1836 to 2020. The paper is based the author’s current research within the Palace of Westminster Restoration and Renewal. It builds on the findings of studies undertaken in parliament between 2016 and 2019, which had focused primarily on the House of Commons, and on his current ongoing research into design and history of socio-technical practices inside the House of Lords. The interviews are used to render visible the design of the current social network, covering the role of both informal and formal actors, and to examine the way they integrated into the technological operations. These offers critical insights into the socio-environmental dimension of the chamber.