Naomi Gibson

Architect and PhD candidate

The Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL

Sophia Psarra

Professor of Architecture and Spatial Design

The Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL

Gustavo Maldonado

Architect and Spatial Data Researcher

MSc Space Syntax: Architecture and Cities, UCL

National parliament buildings have both symbolic and practical roles as seats of power; they define political cultures and contribute to notions of national identity. While political decision-making and governance increasingly take place in a range of spaces and buildings, two historically important spaces – the plenary hall and the parliament building’s site – remain of symbolic significance. These are sites of political theatre, spaces for the formal enactment of debate, voting on legislation, ceremonial addresses and public demonstration. These spaces shape and form the backdrop to forms of political performance which are engaged with by the general public, both in person and through visuals broadcast, published and shared. These are two spaces where democracy at a national level is ‘seen to be done’.

While plenary halls and parliament buildings have been studied, it is rare that these have considered the relationship between the architecture and political culture; how parliament buildings shape political processes and how they express the ideas they stand for. Architectural studies of parliament buildings have typically been straightforward records of plenary hall typologies, architectural styles and forms, without considering how such buildings are performed by politicians and the public. Conversely, social studies of parliament buildings have been largely discursive and not shown how their observations overlay and play out in space. This paper brings together the architectural, spatial, cultural and behavioural, showing the relationships between parliament buildings and people, architecture and events.

Comparative studies of national parliament buildings have also been few. While parliament buildings are seen as expressions of national identities, comparative studies have demonstrated that common threads link different parliament buildings and their processes. Notable examples include XML Architects’ study of the plenary hall typologies of all 193 national parliaments, and Charles T. Goodsell’s 1988 paper The Architecture of Parliaments, which offers a global overview of parliamentary architecture and political cultures. However, while such studies have managed to isolate and demonstrate broad themes that parliaments may have in common, they neglect the nuance and complexity that a deep, multi-layered, interdisciplinary, systematic comparative study can provide, and which this paper looks to provide.

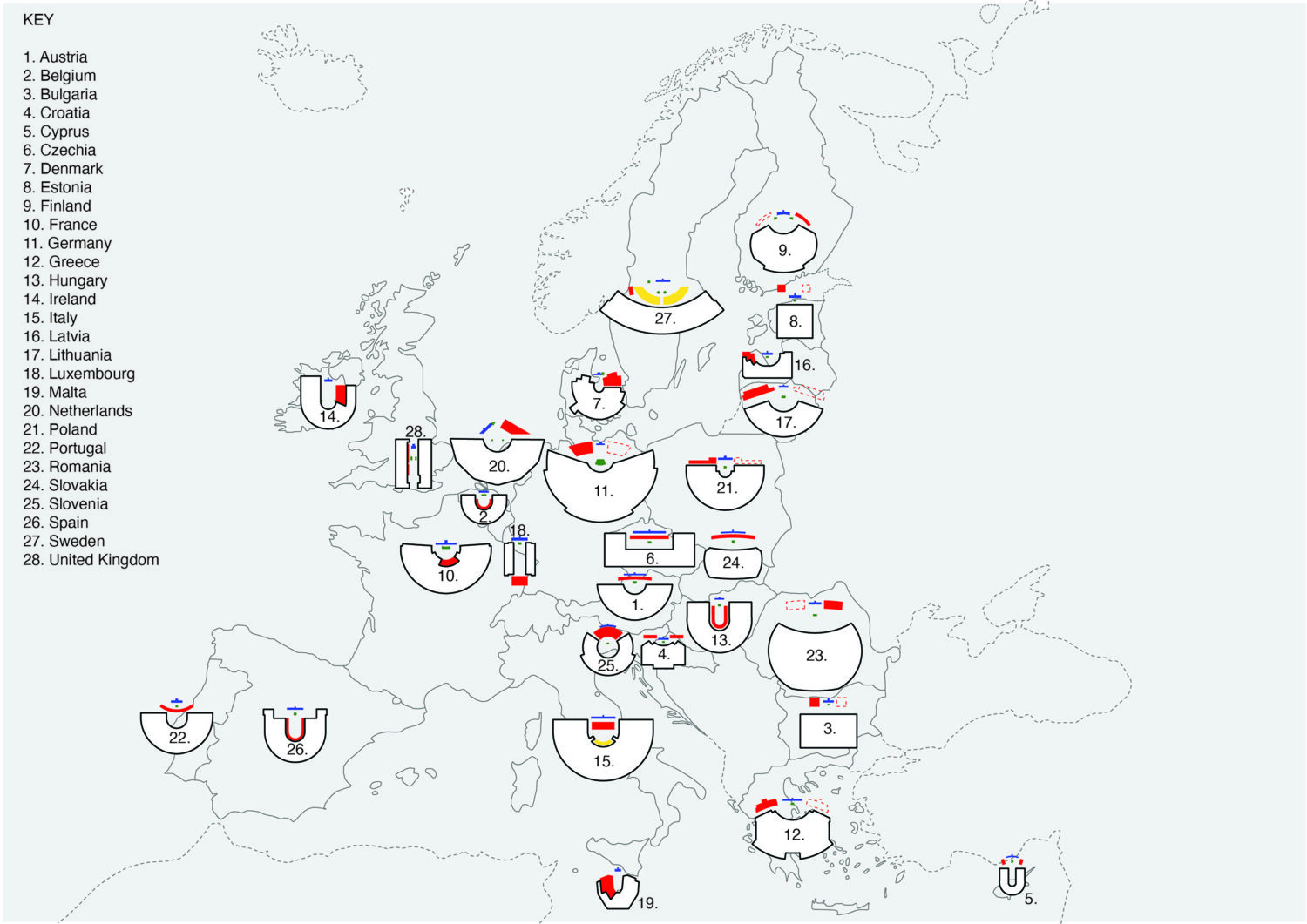

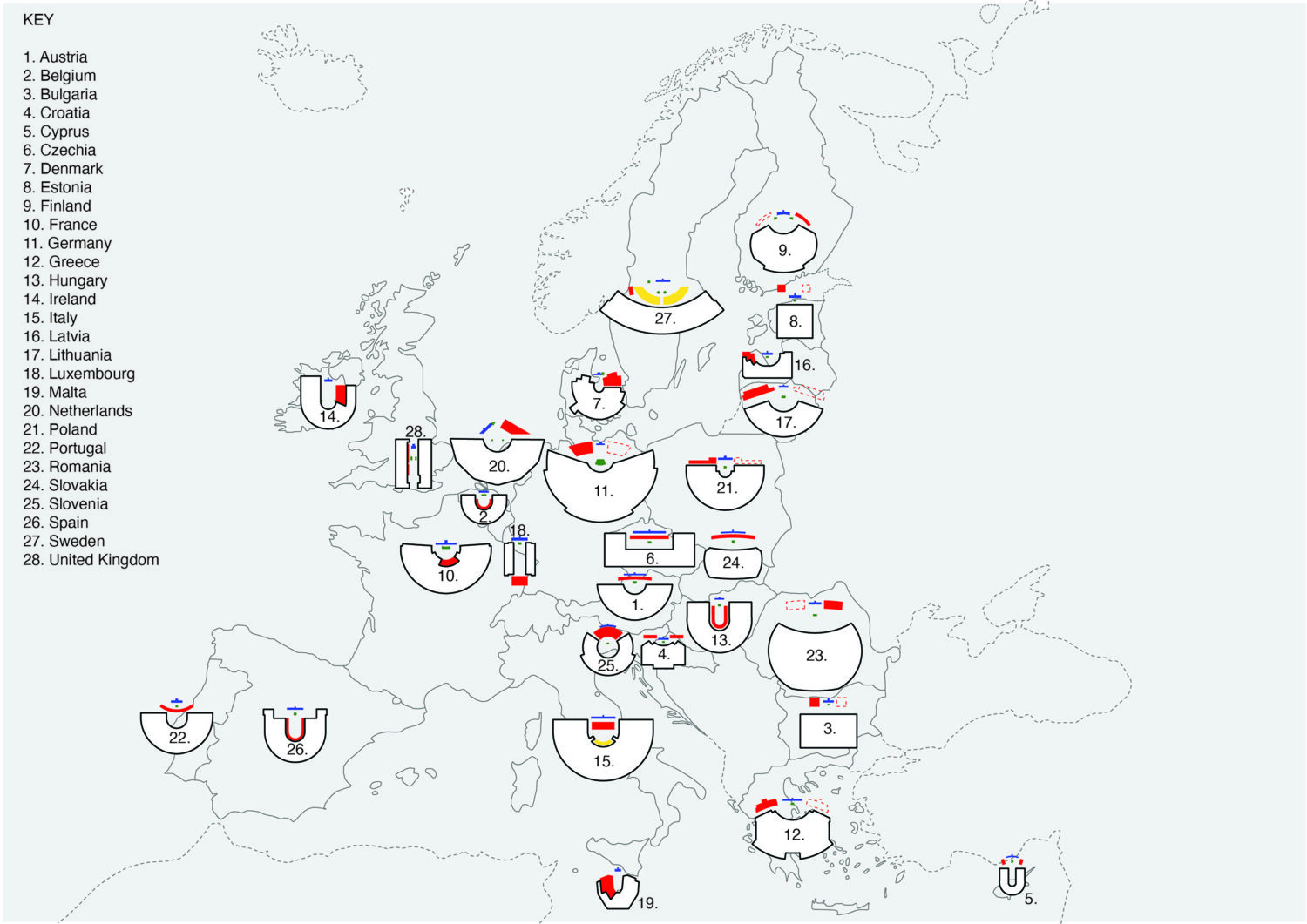

The 28 national parliaments of EU member states including the UK provide a rich testing-ground for this interdisciplinary comparative approach. This is a group of nations with distinct identities, but which hold shared democratic principles as a condition of their membership as well as deeply intertwined cultures and histories.

The paper comparatively considers the expression and spatial shaping of national identities and politics both inside and outside the parliament buildings, primarily through their sites and plenary halls. First, outside, through principal façades, site plans and social-political histories. While considering the web of architectural languages, motifs and public spaces that go some way to define national parliament buildings, one must consider the origins of the building and the social history it is a part of. While some national parliament buildings are purpose-built, others are adapted for the purpose at a pivotal moment in a nation’s history. Some were selected as a temporary home or out of convenience. Some nations, such as Romania and Slovakia, have complex relationships with their parliament buildings, as they are reminders of the earlier, now overthrown, political regimes that built them. The values and ideas expressed by the architecture is not straightforwardly representative of the political values of that specific nation, or a history they wish to symbolise and continue.

Next, inside, through an examination of building plans and parliamentary procedures with a specific focus on the plenary halls. Within the plenary hall, we argue the shaping of political cultures and relationships goes beyond the five typologies associated with seating for parliamentarians – of the opposing benches, semi-circle, circle, classroom and horseshoe. Rather, there isn’t a strict uniformity in the way each typology is performed. This becomes clear when taking into account the spatial relationships between the executive body and parliamentary representatives; where people stand to speak and the location of people they are speaking to; how parliamentarians vote and the visibility of this action; who is allowed to observe these procedures within the space, and where these observers sit.

This paper, by providing a comprehensive visual, spatial and social study of European national parliament buildings demonstrates why interdisciplinary approaches to the study of parliaments matters. It shows how the meaning of parliament buildings can be read through their social-political histories and the political implications of their architecture seen through studying the way in which they are performed. Ultimately, it shows the complex relationship between national parliament buildings and the people they represent.