Harald Trapp

Architect and Exhibition-designer

UAC Skopje

The Teutonic Thing, one of the earliest political forms, is a gathering. It unites the corporate body of the assembled warriors, the place, its marking through stones or twigs, the issues to be negotiated and the process of their consultation and decision. Spatially the circle of the Thing is the interaction of a form of bodies with a form of objects, that distinguishes an inside from an outside. Even if, according to Heidegger, only the “contested matter” seems to have remained in the German word “Ding” (or the English “thing”) from the Thing, in its entirety, as Heidegger writes, it originally intends to “appropriate the fourfold”.

The gathering Thing not only has, but operates through a physical form, though not yet producing an architectural enclosure. Such a space first appears with the differentiation between open-air assembly and enclosed council in ancient Greece and Rome. The latter extends the Thing to the architectural form of the Bule or Curia, now three-dimensionally distinguishing an interior from an exterior space to facilitate a secluded debate. However, the complexity of classical political order proves to be vulnerable in the course of history, overwhelms the structures available and ultimately leads to their dissolution. Historically, therefore, the rule condenses in the king in a kind of regression through concentration, in which the difference between the ruling and the ruled is to be resolved.

Once sovereignty has been concentrated in the hereditary monarch and the metaphysics of divine grace, the king´s two bodies become the Thing, which merely appropriates architecure to supplement its power through representation. To overcome this autocratic rule of a body and with it, the “zoology of the aristocracy” as Marx called it, the French Revolution installs the assembly of citizens to articulate and represent the volonté générale. Extraordinarily, the non-specificity of the national convention´s initial spaces is able to gather the interaction of bodies and objects into a complex architectural system.

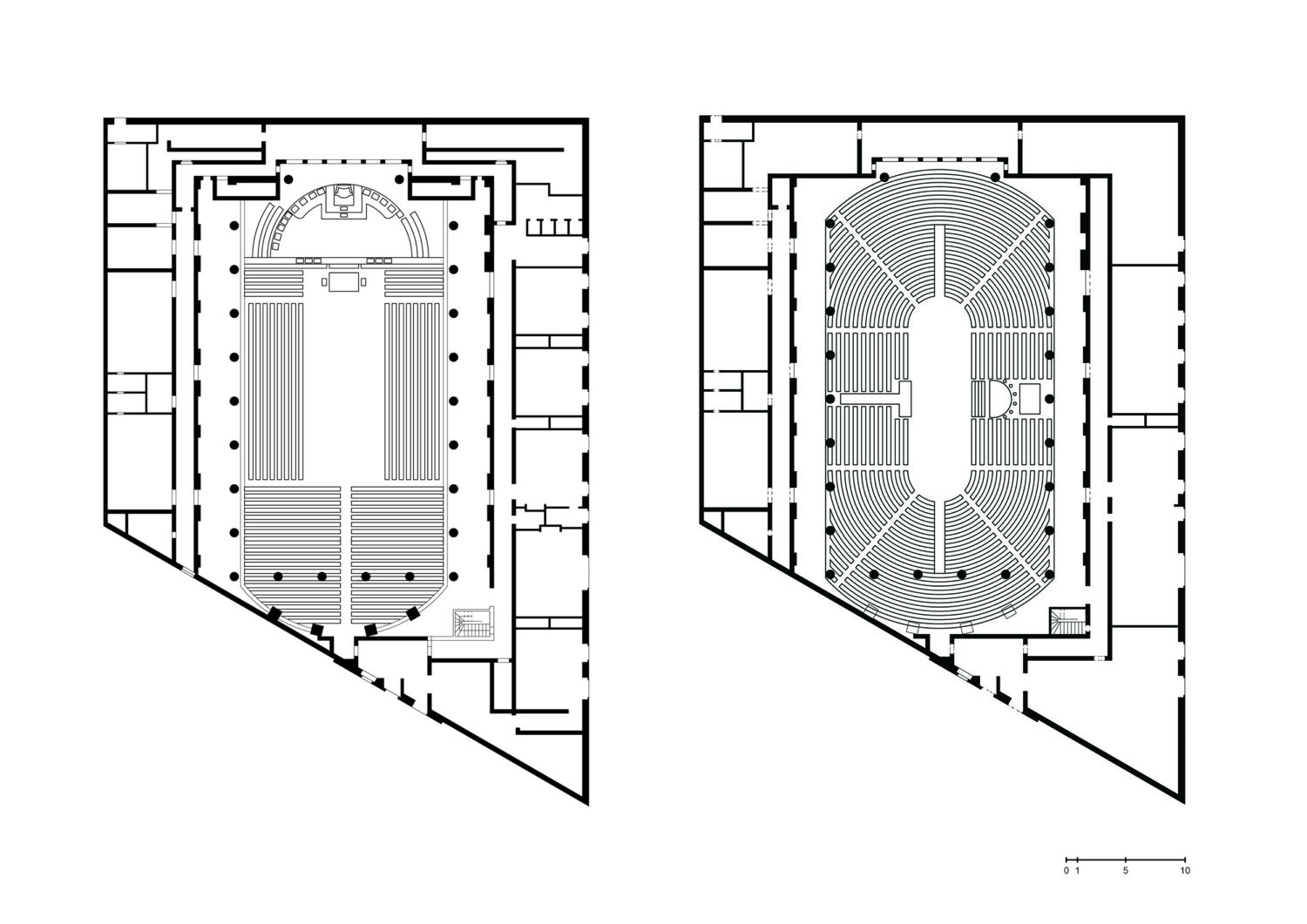

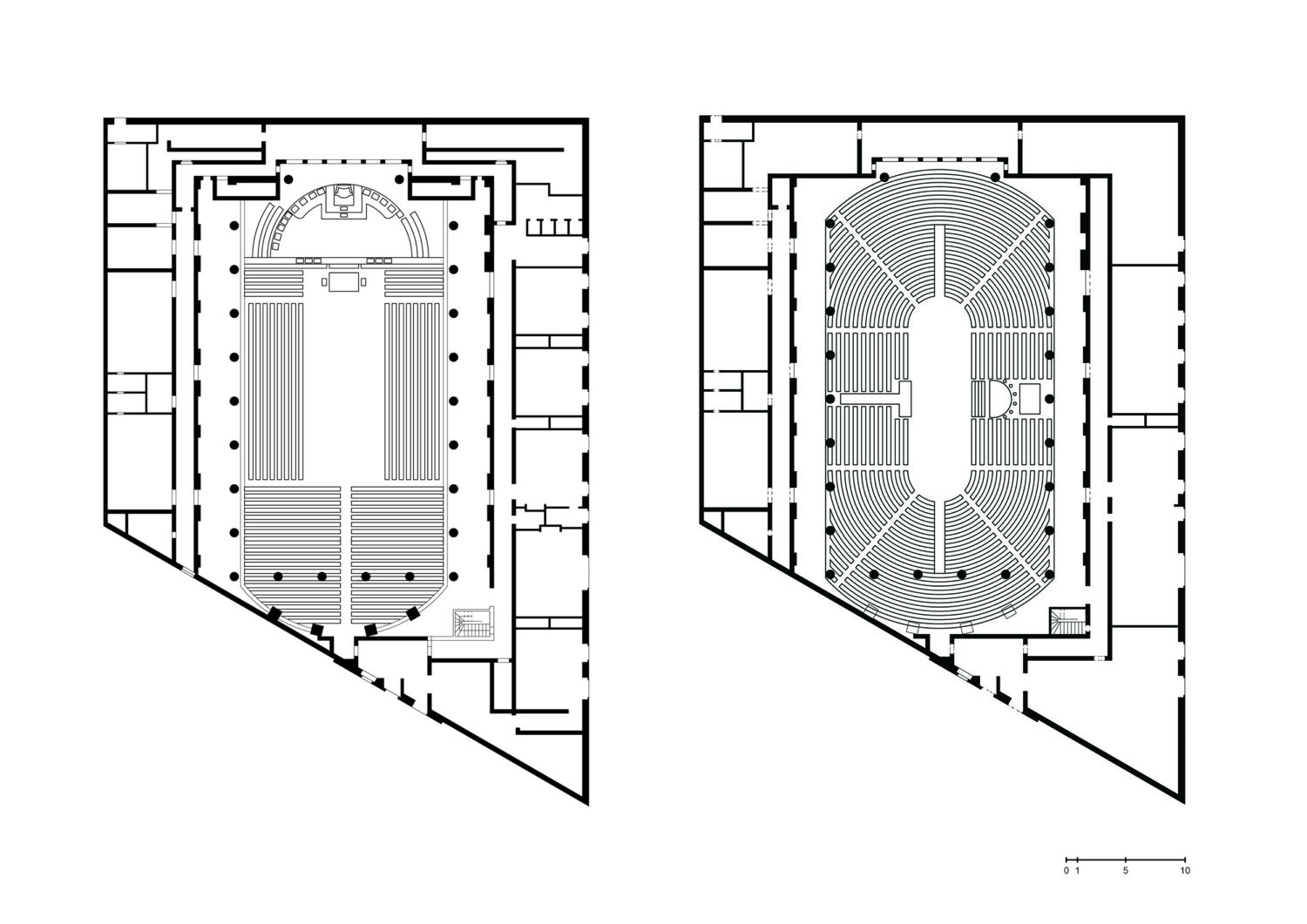

From the Salle de Menus Plaisirs, to Jeu de Paume, Champ de Mars, Salle du Manege and the Salle des Machines an architectural discourse evolves about the relations between the form of gathering, both as the arrangement of the representatives, its spatial reification as an architectural layout, and the production of the general will. The ensuing evolution between the “the circle of discussion and the semicircle of criticism” cannot be reduced to the development of an “environment”, but acknowledges and implements the material gathering as an equal agent in the production of political decisions. During that short period of time, architectural representation is secondary and not explicitly developed, as representational politics equates representativity. Only upon its institutionalisation, the desire to be symbolically represented becomes of growing importance to the National Assembly and a classical facade is added to the Palais Bourbon: the “Thing” finally becomes a monument.

This paper continues the research started in 2014 for our Venice Biennale project “Plenum – Places of Power” at the Austrian pavilion and discusses the connectivity between architecture as a gathering and gathering as a political process. Taking the spatial production of the “general will” during the French revolution as a unique precedent, it investigates the potential of the organisation of representation and the representation of organisation in architecture.