Kerstin Sailer

Associate Professor in Social and Spatial Networks

The Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL

Building layouts have a profound impact on the way humans interact and relate to one another. In his seminal book ‘Space is the Machine’ Hillier argued that “space is more than a neutral framework for social and cultural forms. It is built into those very forms.” (Hillier, 1996, p. 29)

Investigating spatial form in relation to cultural and social phenomena has resulted in a rich programme of research with a focus on a multitude of different building types, such as museums, hospitals, offices and schools. Yet, parliaments have been mostly overlooked to date by space syntax research with some notable exceptions such as a study of the Welsh parliament building.

This paper aims to bring two space syntax theories to bear in the context of parliament buildings: the theory of interfaces and the theory of correspondence and non-correspondence.

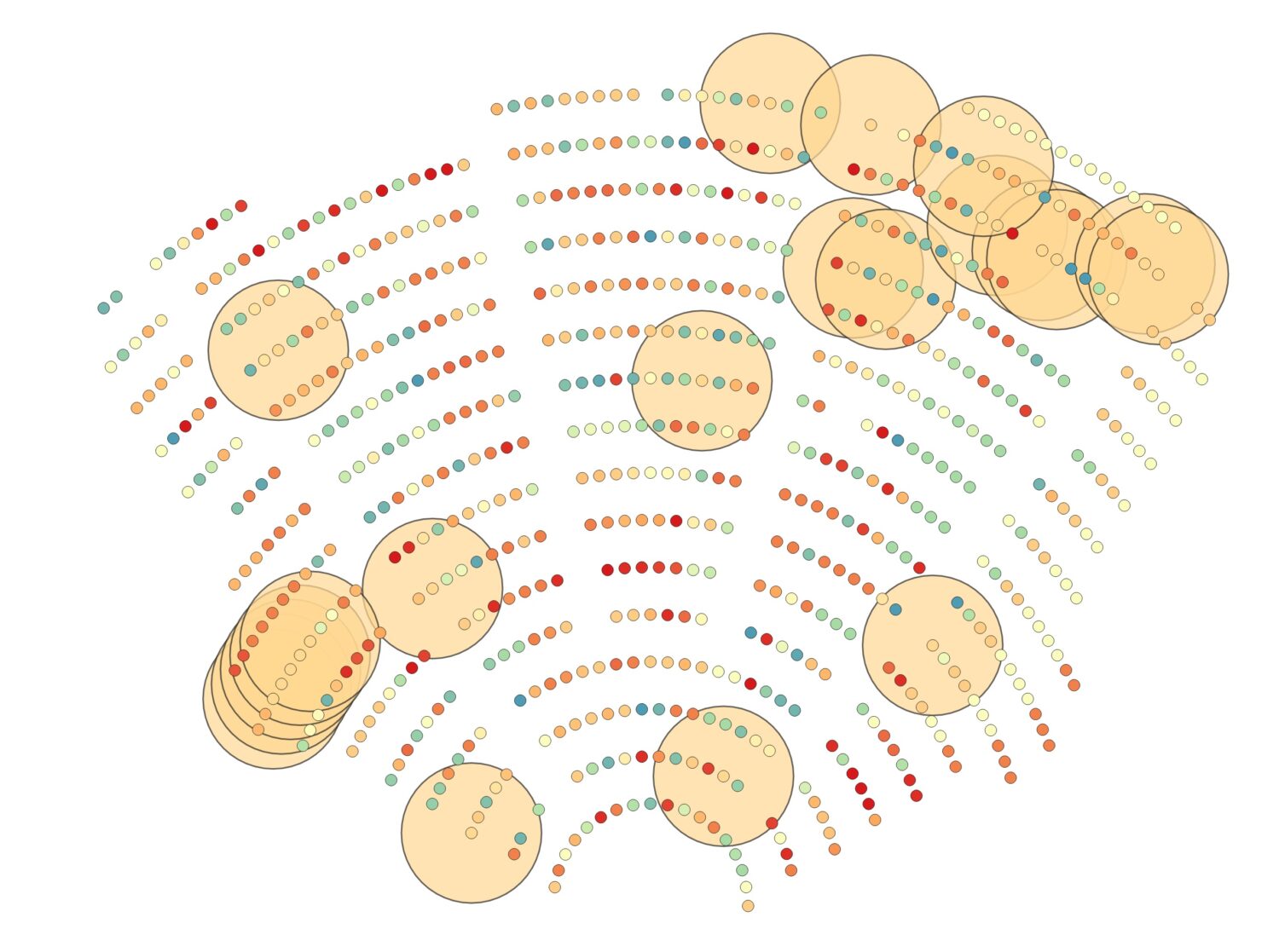

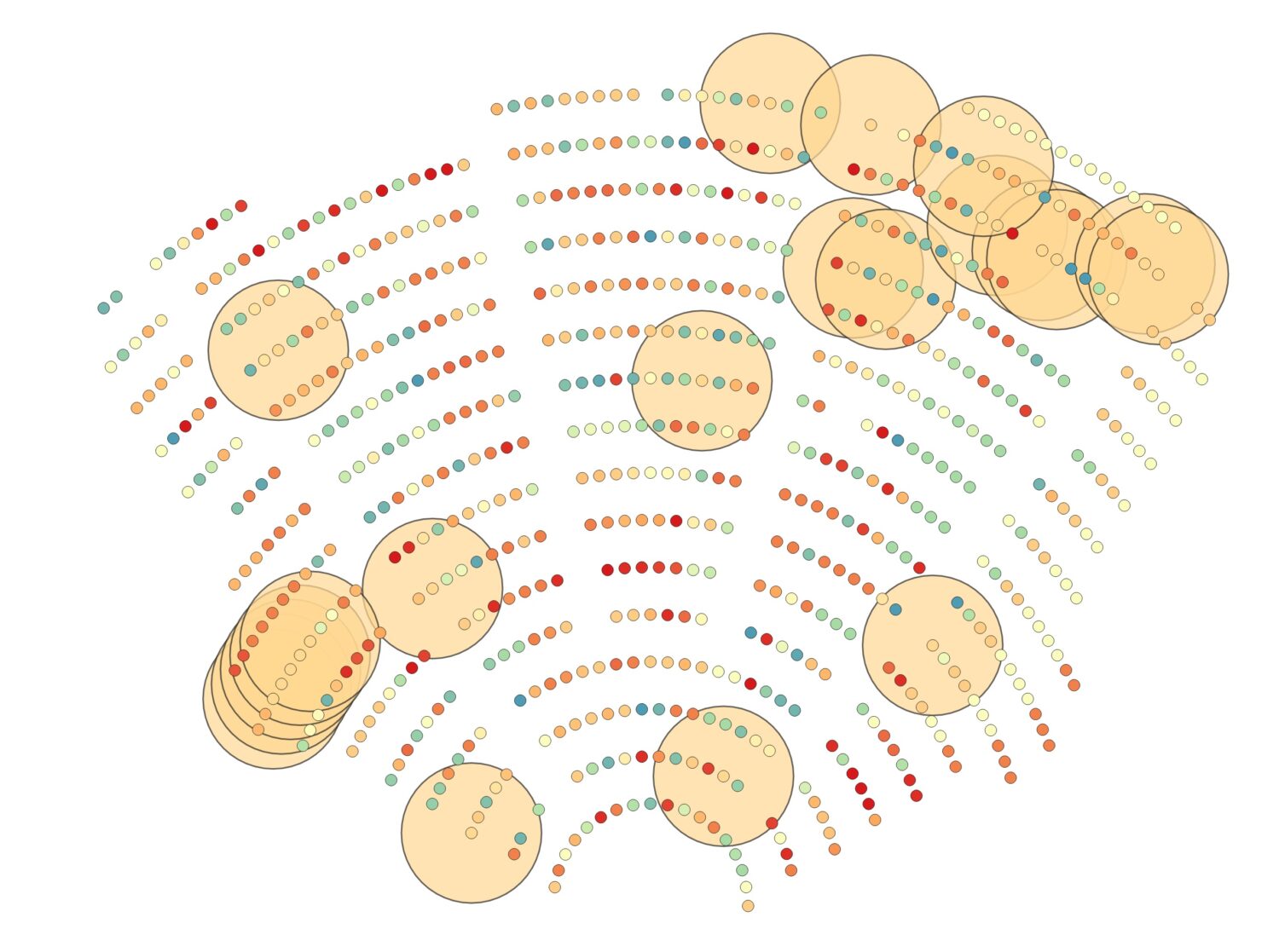

Interfaces, Hillier and Hanson (1984) argued are the relationships between different user groups, mainly visitors (those with temporary usage patterns) and inhabitants (whose social knowledge is inscribed into the building) as orchestrated by built forms. An alternative reading of interfaces was offered by Peponis, interpreting them as distinctive syntactic conditions that are systematically created by a pattern. Those interpretations of interfaces will be taken up in this paper by investigating how buildings create interfaces between different political parties via the structuring of parliamentary spatial layouts alongside seating plans. In particular, partial isovists will be constructed from the seats of parliamentarians in order to analyse the degrees of opposition and cooperation between political parties afforded by building configuration. The plans of the UK parliament versus the German parliament will be used for the analysis. This allows the mapping of two contrasting examples – an opposite bench model as is prevalent in the UK and some of its former colonies, versus the semi-circular model of the German parliament, which is typical of many continental European countries. Taking seating plans into account, Germany presents an interesting example due to its political culture of coalition governments and a spread-out political spectrum of parties reflected in the seating plan.

The second part of the paper builds on the theory of correspondence and non-correspondence, which was defined by Hillier and Hanson (1984) as the overlay between social and spatial relations. Systems where spatial and categorical closeness (such as kinship, class or ethnicity) did not match, i.e. non-correspondent systems were argued to create solidarities thriving on openness, inclusivity and equality. Peponis (2001, pp. xxiii-xxiv) therefore called non-correspondence “a social insurance policy, whereby the strengths deriving from affiliation to social groups are complemented by the strengths derived from affiliation to spatial groups”. This will be investigated using the seating plan and layout of the European Parliament based on visibility and proximity as spatial relations, and fraction as well as represented nation as categorical relation. The degree of non-correspondence in the seating plan can be calculated following the example of workplace seating arrangements as discussed by Sailer and Thomas (2019).

The contribution of the paper lies in the analysis of layouts and seating plans and how they give rise to political cultures with a differential degree of opposition and cooperation built into them.