Kathryn Rix

Assistant Editor Commons (1832-1868)

History of Parliament

In 1847 The Times suggested that ‘in the eyes of the people generally, and of their constituents in particular’, having accurate information about how their representatives voted in the division lobbies at Westminster was ‘of far greater importance than a thousand speeches and the most elaborate displays of eloquence’. For many MPs, not least the numerous silent members of the nineteenth-century House of Commons, their most significant contribution to parliamentary business came not in the visible arena of the debating chamber, but the more confined spaces of the division lobbies. Yet while the physical act of voting with the ‘Ayes’ or the ‘Noes’ took place away from the public gaze, the publication of official division lists from 1836 onwards meant that MPs’ actions within this particular parliamentary space could readily be subjected to scrutiny.

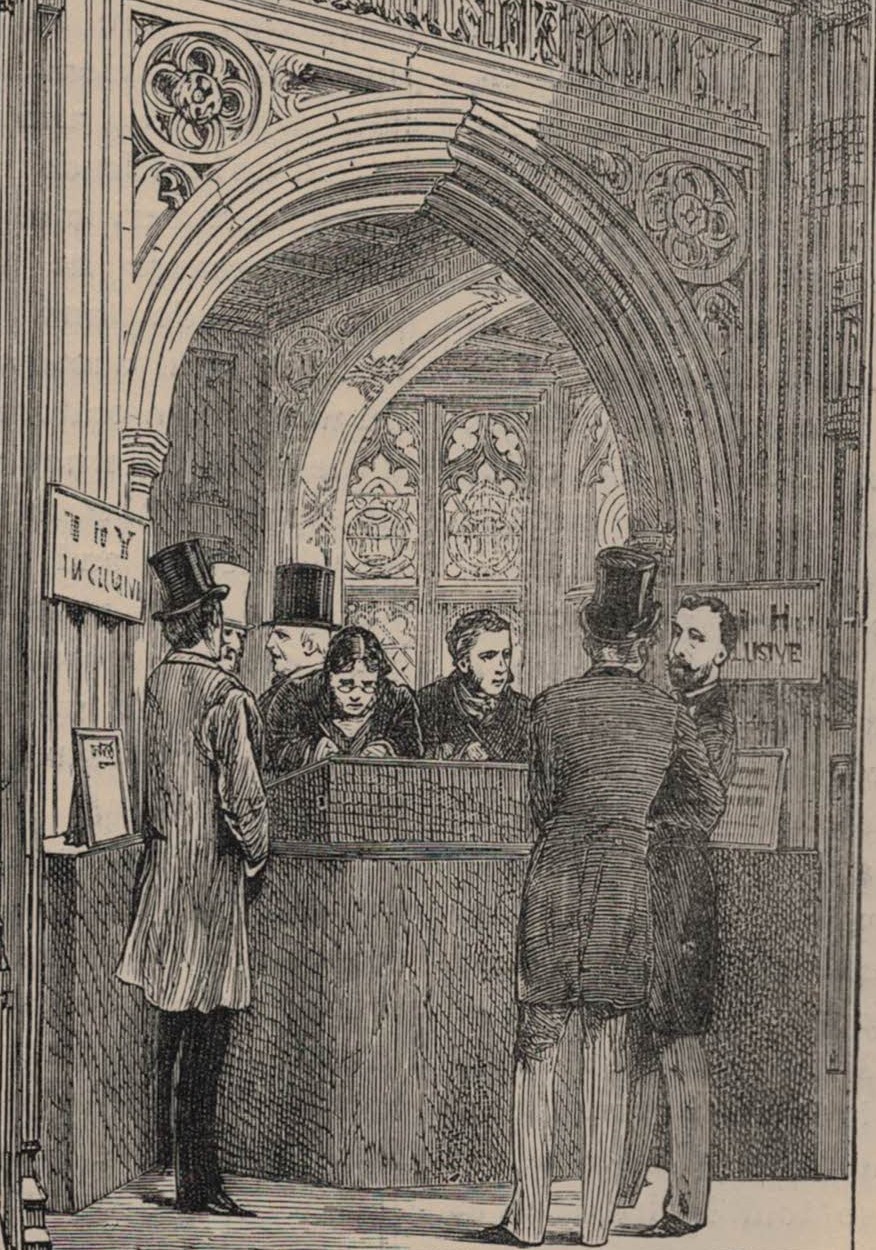

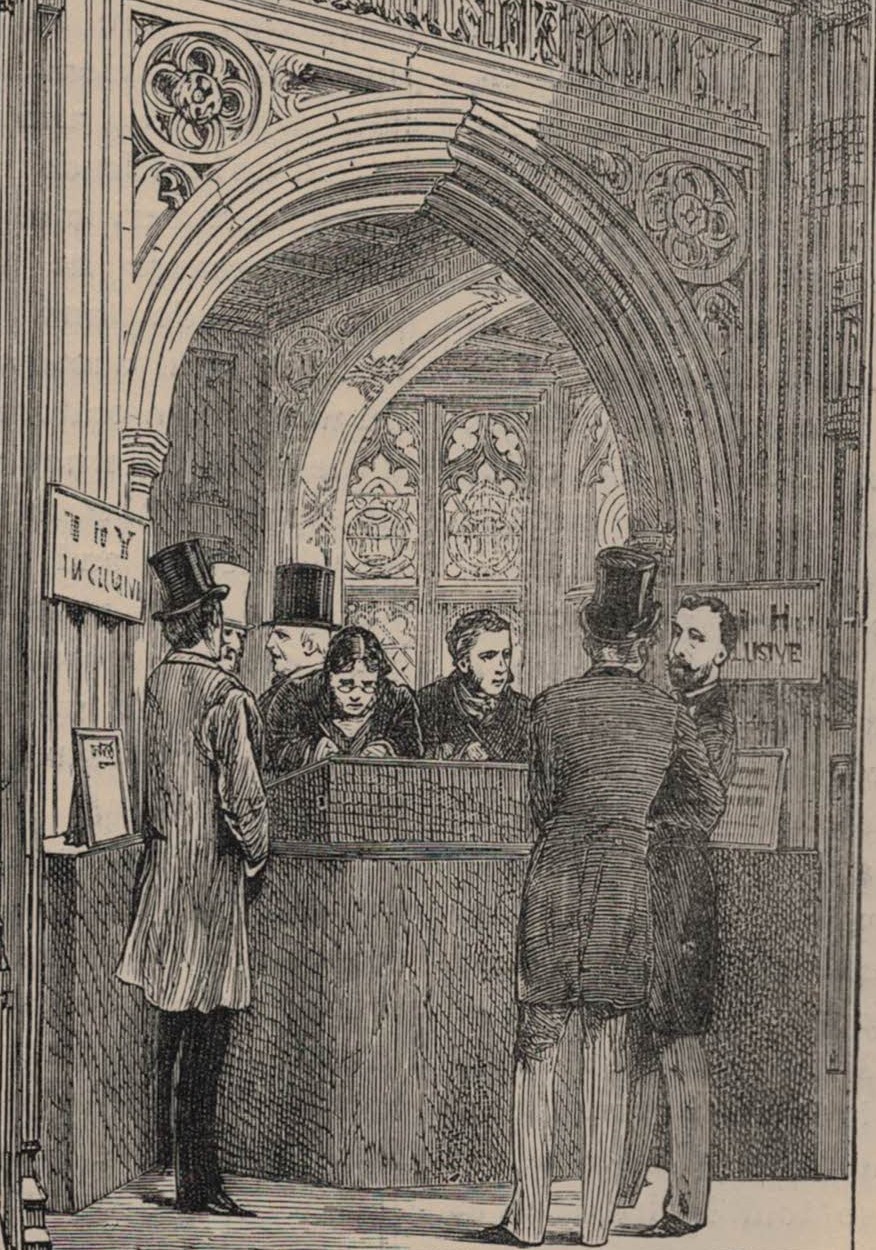

The compilation of more accurate division lists for official publication, in contrast with the unofficial lists previously produced, was facilitated by a significant alteration to the architecture of the House of Commons. In 1836 a second division lobby was added to the temporary chamber in use following the famous fire of October 1834, which had destroyed much of the old Palace of Westminster. Before this date, the presumed minority on any question had gone out of the Commons chamber into a single lobby to vote, while the presumed majority had remained in their seats. The fact that two separate division lobbies first came into existence thanks to this adaptation of Parliament’s temporary accommodation has received little attention in histories of Parliament.

This paper considers the factors which prompted the development of this new parliamentary space, looking in particular at the impact of the 1832 Reform Act on perceptions of MPs’ representative functions. It also reflects on the new opportunities which the temporary House of Commons offered as a site of architectural experimentation and innovation in catering for the needs of 658 MPs in the post-Reform era. Alongside the second division lobby, other new features tried out in the temporary Commons included a separate press gallery and a ladies’ gallery. The two lobby system trialled in the temporary House was subsequently incorporated into the new Palace of Westminster designed by Charles Barry. The division lobbies were among the facilities given a test run in May 1850, ahead of the new Palace’s official opening in 1852. While voting was the key activity which took place within these lobbies, pressure on space on the parliamentary site meant that they also had other, less formal, functions.

Having analysed the reasons for these adaptations to the physical space of Parliament, this paper assesses the ways in which this shaped MPs’ behaviour, both within the confines of the Commons, and in their relationship with their constituents. By enabling the publication of authoritative division lists, the two lobby system focused greater attention on MPs’ levels of attendance (as highlighted in ‘league tables’ published in the press) and their voting record on particular subjects. This had important implications for the development of the two-party system and in shaping the interactions between politics at Westminster and in the localities, key factors in understanding the evolution of the modern British political system.