Murray Tremellen

PhD Candidate Department of History of Art

University of York

Kirsty Wright

PhD Student in History

University of York

In 1610 Sir John Bingley wrote to the mayor and burgesses of Chester with the claim that he was the best candidate for their parliamentary seat due to his ‘nere habitation and dwelling to the Parliament howse [which] ministereth a greater Conveniency… and readines at hand, then to any more remote.’ The proximity he boasted of was afforded by his official residence as Auditor of the Exchequer of Receipt, a house cobbled together from the former buildings of St Stephen’s College in the Palace of Westminster. The house’s medieval walls were adapted by successive occupants, first the Auditors and later the Speakers, as they carved out spaces to facilitate their official role and project their social status. Examination of the house’s function and architectural development helps to illuminate the fluidity of politics in the palace and the changing position of the Auditors and Speakers in relation to the government.

This paper will explore parliamentary buildings as inherited space, through an examination of the changing function and style of the house at St Stephen’s. The first half addresses the life of the house in the hands of the Exchequer officials. Following the dissolution of St Stephen’s College in 1549, its chapel became the first permanent meeting place of the House of Commons. Its re-use as parliamentary space has been charted through the work of the St Stephen’s Chapel project. However, the chapel was but one part of the broader collegiate infrastructure in the palace that included a two-storey cloister, bell tower and range of vicars’ houses. In 1572 these collegiate buildings were granted to the officers of the Exchequer of Receipt and were adapted, at great public expense, to form opulent living quarters and office space. The first part of this paper examines the initial adaptation and use of the buildings as the Auditors carved out private space for themselves and the value of the site as its ownership was contested.

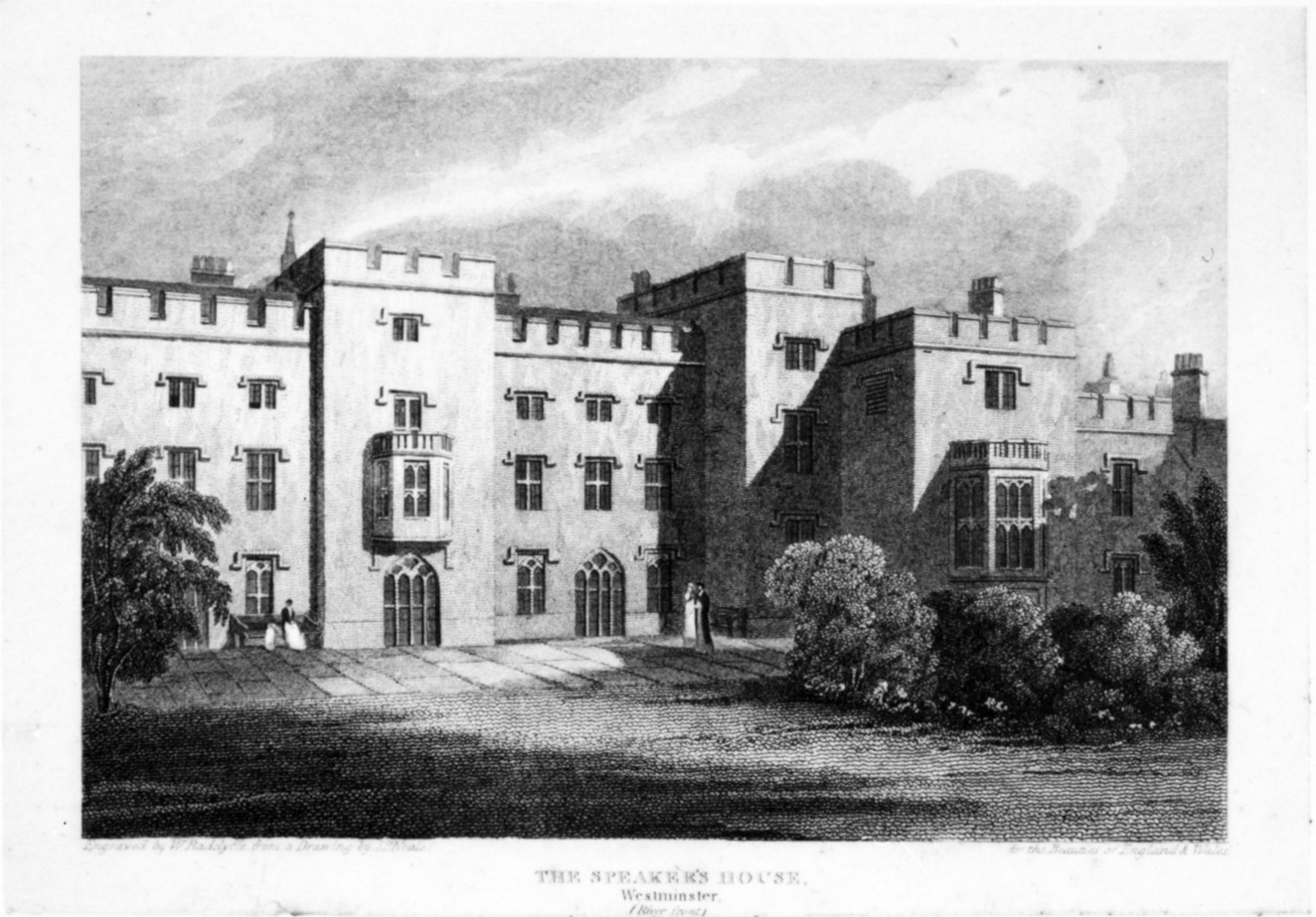

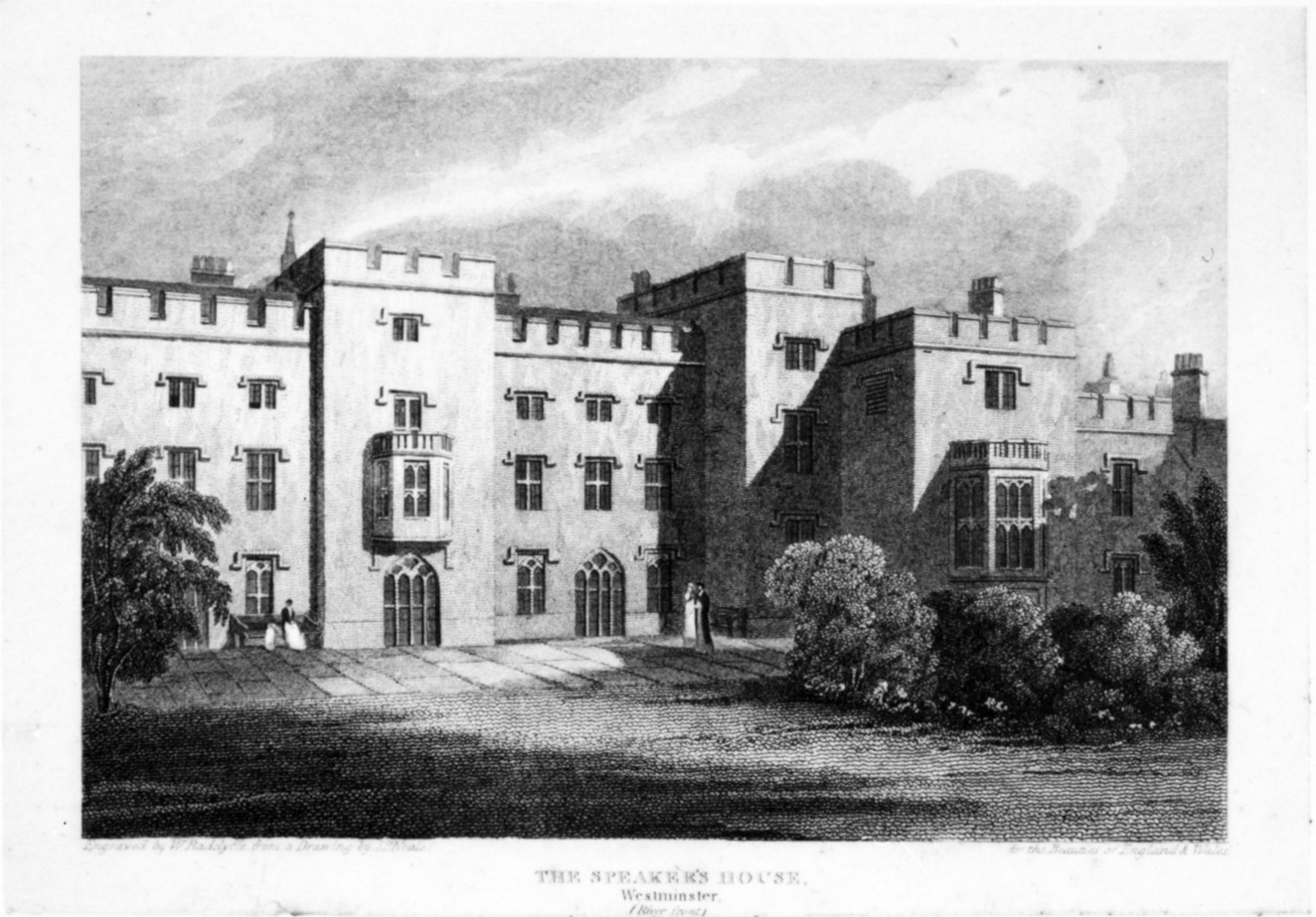

The second half of the paper will turn to questions of style, as we consider the alterations made to the house following its appropriation, in 1794, for the Speaker of the House of Commons. This was the first time that the Speaker had been granted an official residence, and it marked an important advance in the dignity and status of his role. Like the Auditors before them, however, successive Speakers struggled to adapt the medieval and Tudor structures of the house to suit their social and political aspirations at the turn of the 19th century. In a bid to grasp this nettle, Speaker Charles Abbot (in office 1802-17) commissioned James Wyatt, the leading architect of the day, to comprehensively rebuild the house in castellated Gothic style. The Speaker’s House marks one of the earliest uses of revived Gothic for a significant political building in Britain. Its use was partly a reflection of changing fashions, but it also made a powerful statement of Abbot’s vision for the Speakership. Wyatt’s pseudo-medieval architecture helped Abbot to craft a myth of tradition and permanence around the Speaker’s role. This helped him to consolidate his political position and, ultimately, enabled the Speakers to maintain possession of the house which the Auditors had lost.

This paper charts the decline of the Exchequer, one of England’s most important medieval institutions, and the rise of the Speaker, who remains an integral part of modern parliamentary life. The house adjoining St. Stephen’s Chapel played a key role in shaping both institutions, yet its very existence has now been all but forgotten. This paper is a first step to bring the house back into the spotlight, and finally subject it to the critical scrutiny it deserves.